The conflict in Colombia is complex, with a long history and many parties involved. The conflict is often portrayed as a civil war between left-wing guerrilla groups and the state. However, right-wing paramilitary organisations financed by landowners, the business elite, drugs barons and Western oil companies and multinationals also played a significant role in the conflict. Although these (officially) no longer exist since 2006, all kinds of new groups with similar methods have grown up out of these demobilised groups, and these are still causing a lot of violence. The organisations that control the drugs trade also play a major role. Both the guerrillas and the paramilitary organisations finance their wars with drugs money, and in certain areas are closely connected to the drugs trade.

Colombians demonstrate in support of Colombia peace deal while signing ceremony is broadcasted live at Bolivar square in Bogota, Colombia on November 24, 2016. Photo: Lokman lhan/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images.

The underlying causes of the conflict are economic underdevelopment, huge inequality and the unfair distribution of access to land. The war has claimed 220,000 lives and displaced millions. In November 2016 the government concluded a peace treaty with the FARC rebel movement after 52 years of struggle.

FARC stands for Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionaria de Colombia, the revolutionary armed forces of Colombia. This left-wing movement, founded by farmers in 1964, rose up to oppose the capitalist government and big landowners. The ideas of Karl Marx were a leading inspiration in this. Since 1982, the FARC referred to itself as the ‘people’s army’ with the aim of founding a socialist state. Land reform has always been a major goal, but over the years the ideals became muddied; FARC got involved in drug trafficking, earned funds by kidnapping politicians, wealthy landowners and foreigners, and recruited child soldiers. Drug trafficking became the biggest source of income and enabled expansion. The movement provided social services to the population in disadvantaged areas, pulling in more recruits and expanding the group’s influence. The left-wing president Chavez in neighbouring Venezuela actively supported the FARC, including with weapons. FARC was placed on the list of terrorist organisations by the UN, Europe and the USA because of attacks on, kidnapping and murder of civilians.

Thousands of people take part in a demonstration to protest against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) leftist guerrillas and to ask for the release of hostages, at Bolivar Square in Bogota on July 20, 2008. AFP PHOTO/Inaldo Perez.

But gradually the FARC’s power started to wane. In February 2008 a mass protest was organised against kidnappings by the FARC. In the same year, three of the seven highest-ranking FARC leaders died. Following two abortive attempts, in 2012 President Juan Manuel Santos’ government entered into peace negotiations with the FARC. After four years of negotiating, in November 2016 the peace agreement was signed by both parties.

Members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas watch TV at the “Alfonso Artiaga” Front 29 FARC encampment, January 16, 2017. The FARC’s 5,700 fighters are now in camps waiting to be transferred to UN-monitored ZVTN transitional zones where they will demobilize and begin their path to civilian life and legality over a period of six months. AFP PHOTO / LUIS ROBAYO.

As a response to the government’s failing security policy, which proved inadequate in combatting the left-wing guerrilla groups, a third major player in the Colombian conflict emerged: the paramilitaries. These legal, heavily armed private militias were financed by big landowners, drugs barons, industrialists and Western oil companies and multinationals to protect themselves from the guerrillas.

The leader of the paramilitaries was Carlos Castaño, who took up arms at the age of 16 when his father – a big landowner – was kidnapped and murdered by the FARC. Castaño, who was suspected of being a member of the Medellín Cartel, openly admits that 70% of the group’s income came from the drugs trade. As the drugs barons grew rich and invested in property, villas and land – driving out small famers – the paramilitaries became their natural allies, offering protection from the guerrillas.

A government soldier sits atop a tank 18 October 2002 keeping a watchful eye over Comuna 13, a neighborhood of Medellin. Medellin was rocked by violence since the governments decision two months ago to recapture a sector of the city disputed by right-wing paramilitaries and militias. Fifteen people were killed and 20 were injured in Operation Orion ordered 16 October by President Alvaro Uribe. EPA PHOTO AFPI / FERNANDO VERGARA.

During the past 15 years, right-wing paramilitaries have been accused of large-scale human rights violations, kidnappings and the execution of enemy combatants and civilians suspected of supporting the left-wing rebels.

In the early part of the twentieth century, Medellín was Colombia’s industrial powerhouse. This region produced the most coffee and the textile industry flourished; it also has huge supplies of raw materials and minerals. The ensuing prosperity attracted banks and service-providers as well as people from all over the country looking for opportunities: between 1950 and 1973, the region’s population trebled.

Things started going downhill in the 1970s: as the region’s industries were struggling to compete with Asian countries, the railway that connected this city in the Andes to the sea (and the rest of the world) was destroyed. All the while, more and more people kept pouring into Medellín. Because of the opportunities the city offered, but also because of the armed conflict in the rural areas. At the very moment demand for work was at its height, the industries failed. Factories closed down and by the 1990s the city had plunged into a deep crisis: unemployment was running at approximately fifty percent, resulting in extreme poverty and inequality.

The history of Medellín is one of a typical industrial city that got caught up in problems caused by the drugs trade and a civil war. And on top of all this, we had Pablo Escobar, as they say in Medellín. All over Colombia unemployment, war and drugs-related violence raged – then this man stepped up and made a bad situation even worse. In the 1990s, Medellín became the murder capital of the world.

‘Because he’s from Medellín,’ is the answer you will hear in this city. Medellín has a history of smuggling and illegal trade that experts have attributed on the one hand to the city’s strategic location – it is linked by rivers to the sea – and on the other to the character of the Paisas, as the inhabitants of this region are known.

Bodyguards of Pablo Escobar, 1988.

Paisas are famous for their enterprising nature, ambition and persistence. Like Pablo Escobar. Leaving aside all the murders and attacks for a moment, he was one of the greatest business geniuses of his generation.

From the private archive of Pablo Escobar’s son, Pablo on a Jetski on Hacienda Napoles, early 80s.

Escobar was the first to think of buying in better quality coca from Peru and Bolivia, processing this in Colombia and then selling it on to the United States. At the height of his power, 80 percent of the cocaine in the United States came from Medellín – making Escobar the second richest man in the world, with an estimated fortune of 30 billion dollars. Some of which he then ‘shared out’ in the city’s poor neighbourhoods.

The death of Pablo Escobar on 2 December 1993 is often seen as the turning point for Medellín. But this is only part of the story. Escobar’s death did mean the end of the big drugs bosses who could stand for election to the congress and who were more or less untouchable, but for years afterwards Medellín remained the most dangerous city in the world. During the 15 years leading up to 1993, 45,000 people were murdered, and that number remained the same during the next fifteen years.

After Escobar’s death, the Medellín Cartel fell apart and the cocaine business fragmented. Other cartels, paramilitary and guerrilla groups fought for power. Carlos Castaño and Don Berna, leader of Los Pepes – a collection of enemies of Escobar – set up their self-defence militias in Medellín. Whereas in Escobar’s day it was ‘in’ to be a contact killer, after his death young people joined these paramilitary ‘milicias’ that were set up as a response to the violence dished out by youth gangs and drugs dealers in the poor neighbourhoods on the hillsides, where the police and army hardly dared go. There was a saying in Medellín – the only law that applies on the mountainside is the law of gravity.

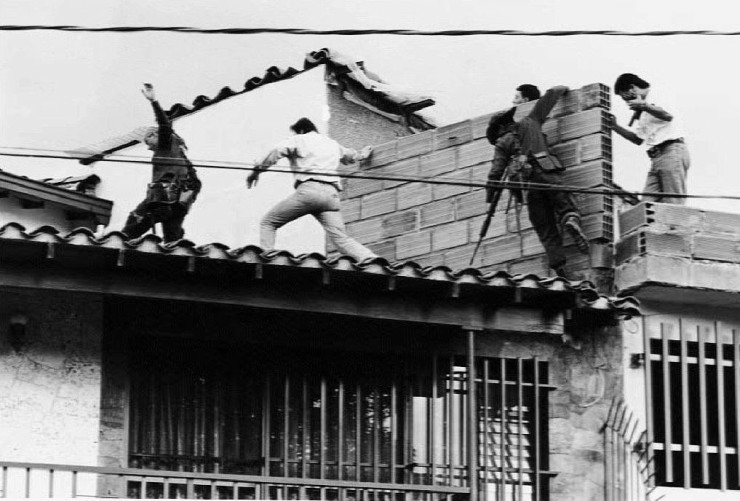

Colombian police and military forces storm the rooftop where drug lord Pablo Escobar was shot dead just moments earlier during an exchange of gunfire between security forces and Escobar and his bodyguard, 02 December 1993. The death of Escobar and the bodygaurd ends a 16-month hunt for Escobar.

In the meantime, the political and social transformation undergone by Medellín had already started before Escobar’s death when important sectors in the city set up a civil network to meet the challenges present by the Cartel. At the height of the crisis – in 1991, the most violent year in the city’s history – universities, NGOs, politicians, unions, entrepreneurs and citizens’ organisations united to look for a way out for Medellín. This formed the basis of the co-operative economy that is giving Medellín an advantage over other Latin American cities to this day.

Things really changed in Colombia from 2002, when Alvaro Uribe was elected president. His promise to effectively tackle the armed groups in particular ensured that he won the election. Uribe believed that the state should provide security, not the paramilitary groups. He put residential areas and roads under the control of the army, concluded disarmament agreements with the paramilitary groups and freed the most high-profile FARC hostage: Ingrid Betancourt. At the end of his first term, defence spending had doubled and there were 25 percent more soldiers and police. The number of murders fell by 43 percent in 2006 compared to 2002, and the number of kidnappings for ransom by 82 percent. Uribe was a hero, and for the first time in many years Colombia was a safer place. What’s more, under his regime the economy started to pick up and foreign companies started investing in Colombia again.

‘Operation Check’ freed Colombian presidential candidate Ingrid Betancourt and 14 other FARC hostages on 2 July 2008. EPA/DISCOVERY CHANNEL / KAREN SALAMANCA.

But Uribe is also controversial. Some of the 20,000 guerrilla fighters who left the FARC during his time in office turned out not to be guerrillas at all (soldiers killed civilians and then dressed them in rebel uniforms). And it turned out that dozens of Uribe’s allies, including his cousin, had close ties to right-wing paramilitaries. Also, human rights violations by the army increased greatly under Uribe.

In 2006, Uribe was elected president for a second time. In 2010, he was succeeded by his Minister of Defence, Juan Manuel Santos.

On 26 September 2016, the government and the FARC signed a peace agreement under the supervision of the head of the UN Ban Ki-Moon and various heads of government. A few days later, a narrow majority of the population rejected the peace agreement in a referendum. Most of the ‘no’ votes came from the Antioquia Department and its capital, Medellín, where the ‘no’ vote received 62 percent of the votes. In particular, the part of the deal that said that former fighters wouldn’t be punished for murders, attacks and drug trafficking provided they confessed to these crimes – that they would have to do community service instead of going to prison – proved unacceptable to the voters. They were also against the possibility of the FARC getting seats in parliament without elections being held first.

That these sentiments were even stronger in Medellín was due to the popularity of the leader of the ‘no’ camp – right-wing conservative senator Alvaro Uribe. He is from Antioquia and harbours a great hatred of the FARC – partly because his father was killed by the guerrillas in 1983. Uribe was president of Colombia from 2002 to 2010 and acted ruthlessly against the rebels. This quickly reduced the number of kidnappings and attacks taking place, and many people in Medellín still see him as a hero because of this. They supported his view that rebels deserve a prison sentence instead of seats in parliament.

President Santos sat down and negotiated with the ‘no’ camp and then went back and made a new, amended proposal to the FARC. In November 2016, a new agreement was reached. There was no vote this time.

The treaty contains agreements on the redistribution of agricultural land, compensation for victims, political participation by disarmed rebels and joint termination of the drugs trade. The most hotly debated topic was the punishment of war crimes. It was agreed that the parties to the conflict would be judged by a specially convened peace tribunal. Those who admitted to their crimes would have to perform community service for a period of five to eight years. This could include partial restrictions on their movement, but the perpetrators would not have to go to prison.

President of Colombia Juan Manuel Santos (L) and Chief of the FARC Rodrigo Londono Echeverry a.k.a. ‘Timochenko’ (R) shake hands after signing the new peace agreement to end 52 years of internal armed conflict in the country, in Bogota, Colombia, 24 November 2016. EPA/MAURICIO DUENAS CASTANEDA

After the people rejected the first version of the agreement in a referendum, negotiations resumed. In the final agreement, the FARC was obliged to surrender all of its property: this was a major demand from the ‘no’ camp. In addition, the peace treaty was not incorporated into the country’s constitution, leaving the way open to further amendments in the future. Former guerrillas would also not automatically be granted immunity from prosecution for drugs trafficking.

One of the major reasons for the conflict was inequality. More than fifty years of struggle have done little to change this. Colombia has taken great strides in reducing poverty: between 2002 and 2014, 6 million people worked their way out of poverty, and according to the World Bank for the first time in history there are more Colombians with a middle-class income than living in poverty.

Nevertheless, Colombia occupies the number 8 position in the top 10 most unequal countries in the world. One percent of the Colombian population earns twenty percent of the national income, and the richest ten percent earn half of this, French economist Thomas Piketty writes in his bestseller ‘Capital in the Twenty-First Century’. To make the calculations, he used the income tax figures from 1993 on. For comparison: in Europe, the richest ten percent of the population earn 30 to 35 percent of the Gross National Product; in the United States it is 45 percent.

Almost all Colombians (85%) are aware of the unequal distribution of income, and three-quarters think the government should take measures to better distribute the nation’s wealth.

Medellín is the most unequal country in Colombia. 14 percent of its residents live in poverty, and 8 percent in extreme poverty. This number has fallen by a a quarter since 2000 and is considerably lower than in the rest of the country, where almost one third live in poverty. The policy of investing in the poor neighbourhoods and stimulating education and entrepreneurship has generated more jobs, meaning poverty has decreased. However, the city’s growth has also generated great wealth; true, the poor have become a little less poor thanks to this, but above all the rich have become richer.

Piketty argues for a more progressive tax regime which instead of increasingly taxing work, principally taxes property and assets. ‘The most important thing is that politicians and the elite realise that social and fiscal reforms are necessary for sustainable growth and peace,’ he said during a lecture in Bogota. ‘In Europe and the United States, this has led to considerable friction and economic crises. Colombia can avoid this by changing now.’