Aung San Suu Kyi is a Burmese politician and leader of the National League for Democracy. She has been acting as an advisor to the state since her party won the elections at the end of 2015. She cannot become president as the constitution states that the president may not have any family members who are foreign nationals. Suu Kyi was married to British academic Michael Aris, with whom she has two sons.

Aung San Suu Kyi arrives for Myanmar’s first parliament meeting after November 8’s general elections, at the Lower House of Parliament in Naypyitaw November 16, 2015. REUTERS/Soe Zeya Tun

Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the NLD, also won an election back in 1990, but instead of becoming president she became the most famous political prisoner in the world. The defeated generals ignored the election results and in the thirty years that followed, they did everything they could to silence Aung San Suu Kyi. They placed her under house arrest, tried to demonise her and to make people forget her.

The detention of Suu Kyi was to some extent voluntarily, and this is one of the things that explains its popularity among the Burmese. At any time of her years of house arrest between 1989 and 2009 , she had the choice to leave Myanmar to her family in England. However, that would have meant she could never return and she would have to give up her ideals. She did the opposite and gave up her roles as a mother and wife instead. Even when her husband was dying of prostate cancer she didn’t dare visit him, or even attend his funeral.

Suu Kyi was released on 13 November 2010. Her release was part of the reforms introduced by the junta – which at the same time instigated relations with the outside world and released political prisoners. The euphoria concerning her release caused the world to forget the so-called ‘democratic’ elections of a week previously, which kept the military in power.

Aung San Suu is the daughter of a national hero in Myanmar, Aung San, who is seen as the national hero because of the role he played in negotiations with the British about Burma’s independence. He was murdered by opponents shortly before independence was achieved. Almost every house in Yangon has his photograph on the wall. Alongside one of his daughter.

‘Saffron Revolution’ refers to the protests by Buddhist monks in 2007. Monks have always played an important role in the democracy protests. They led demonstrations against the British colonial regime and supported the students during a mass protest against the junta in 1988.

Monks and civilians gather in a street in Yangon/Myanmar, 26 September 2007. Myanmar troops used batons and tear gas Wednesday to keep tens of thousands of marching monks and their layman followers out of Yangon’s holiest shrines in a standoff between rifles and rust-coloured robes that is expected to end in bloodshed. EPA/DEMOCRATIC VOICE OF BURMA

In 2007, tens of thousands of monks demanded the release of political prisoners, democracy and an end to inflation. They were supported by civilians in Yangon and Mandalay. After a month of protests, the junta responded with heavy-handed repression. More than 2,000 people were arrested and monasteries across the country faced severe terror. According to the Burmese media, more than one hundred demonstrators were killed.

There is no straightforward answer to this question: what the junta says can’t be taken as indicative of its actual motives. A good example of this is the elections of 2010, which were presented as the end of the military regime – but which in fact merely served to consolidate its power. The parliament was made up of former members of the military who simply swapped their uniforms for suits.

Observers and human rights organisations point out that the reforms were not the result of pressure or protests from below, but part of a carefully planned process, the basis for which was laid in 2003 – the year the junta announced a ‘road map’ towards a democratic, modern, prosperous Myanmar. This road map led to a new constitution, adopted in 2008, and to the elections of 2010.

Another reason often given is that its dependence on China was problematic for the nationalist regime. Although China provided support to the junta, this made Myanmar heavily dependent on China – including in economic terms. Sanctions imposed by Europe and the United States meant that Myanmar’s military rulers depended on trade with China. The reforms were aimed at strengthening ties to the West, thereby reducing this dependence on China. In addition, the economic system is clearly designed in such a way that the profits it generates mainly benefit a very small group (the military), so there is clearly a motive of personal enrichment behind the reforms.

The reforms did however ultimately lead to free elections in 2015 and a glorious victory for the opposition. Aung San Suu Kyi still has limited space in which to operate, but it is hoped that she will be able to implement change and put an end to the economic monopoly of the old military elite.

In November 2015, Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy, won the first free elections in more than 50 years (not counting the elections of 1990 because the result was ignored by the regime). Nevertheless, Myanmar is still not a democracy, for three reasons:

Election day, November 8, 2015. Julius Schrank.

Five years after the regime announced reforms, the question was asked: what has changed? The answer from the inhabitants of Yangon, international observers and NGOs alike was: too little.

True, American and European sanctions have been reduced and the country is awash with trade missions, foreign investors and tourists. All the big consultancy firms can be found in the new office blocks in Yangon: from KPMG to PriceWaterhouseCoopers. Since 2011, Yangon has been one big traffic jam and more people own smartphones in Myanmar than have electricity in their homes.

For the local population, little has really changed, however. The regime neglected the infrastructure and heath care, and since the universities were closed following the student protests in 1988, education has been largely dormant.

In the meantime, huge ‘economic zones’ are being built on the periphery of Yangon – including a new port. These should create jobs. Not well-paying jobs as yet – neglect of the education system means there is a great shortage of well-educated workers. For the first time in fifty years, however, there is the prospect of a better future, and this is boosting hope and motivation. But it will take time before the economic improvements reach everyone.

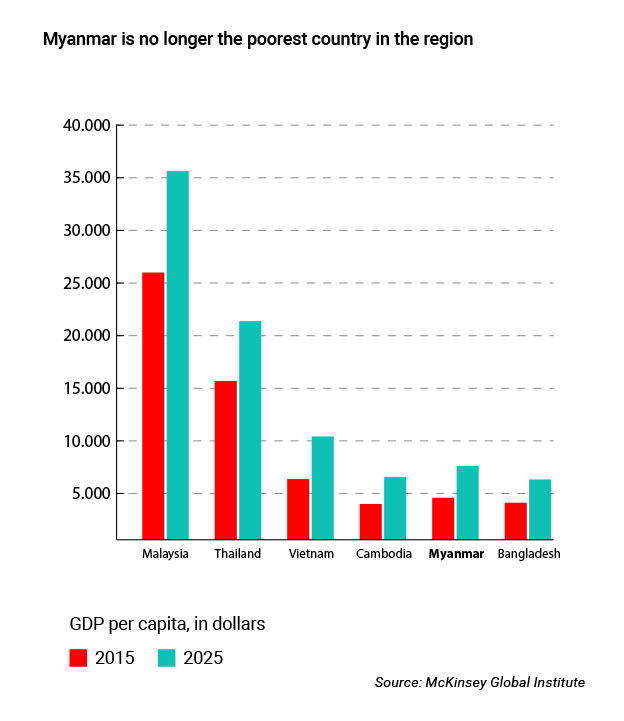

From the moment the democratisation process started, Myanmar has been seen as a promising economic proposition. After fifty years, the borders suddenly opened, sanctions were lifted and investors descended on Myanmar en masse. It’s not difficult to see why: the country occupies a strategic location between two economic powerhouses (China and India). While the populations of surrounding countries such as Thailand are getting older and more expensive, Myanmar is a country full of young, cheap labour. Then there is the long coastline (the Netherlands has already sent a ‘fishing mission’); the fertile soil (before the military coup, Myanmar was the biggest exporter of rice in the world); and an abundance of raw materials, from gold and jade to oil and gas.

In addition, after years of isolation, there is a need for all kinds of stuff: from tampons to mobile phone cards. Myanmar has the fastest-growing internet market in the world. Since two foreign telecom companies entered the market at the end of 2014, a sim card that five years ago cost 850 dollars can be bought on the street for 2 dollars.

Myanmar is one of the poorest countries in the world, with an average annual income of 1,200 dollars – compared to 83,700 dollars in Singapore and 44,320 dollars in the Netherlands.

An extremely low income level, particularly when you think that, until the middle of the twentieth century, Myanmar was the second most prosperous economy in Southeast Asia thanks to the lucrative trade in rubber, rice, wood and opium. In 1962, a military coup led by general Ne Win set aside the constitution. The generals banished Western organisations and carried out sweeping nationalisation plans under the banner of the Burma Socialist Programme Party. This had devastating consequences for the economy, which had all but ground to a halt by 1987.

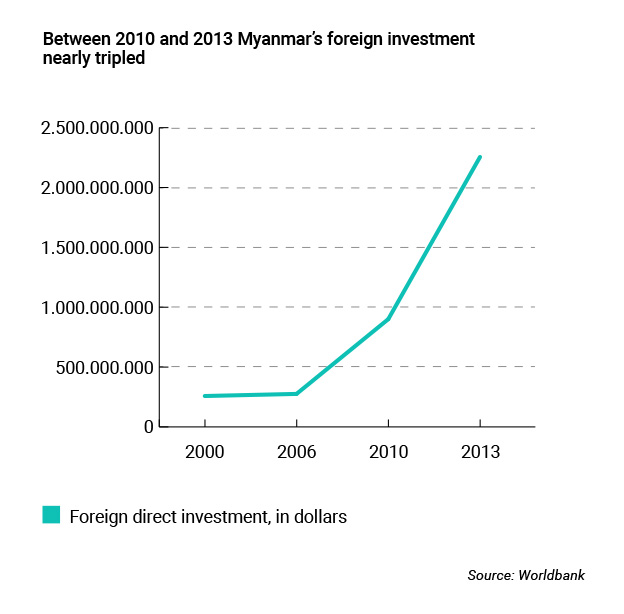

Since the start of the democratisation process – which experts believe was initiated for economic reasons – the economy has grown by 7 to 9 percent a year. Foreign investment in Myanmar tripled between 2010 and 2013.

According to Wealth-X, a consultancy that examines worldwide wealth, there are 40 ultra-rich people in Myanmar (possessing more than 30 million dollars). This number is set to grow by a factor of seven over the next ten years – faster than anywhere else in the world.

Naypyidaw has been the capital of Myanmar since 2005. This is a completely new city, 300 kilometres north of Yangon. Far from the water – it is said the junta feared an invasion by the United States – and from the volatility of Yangon.

Members of the Myanmar military parade during ceremonies marking Armed Forces Day in Naypyidaw, 27 March 2007. AFP PHOTO/Khin Maung Win

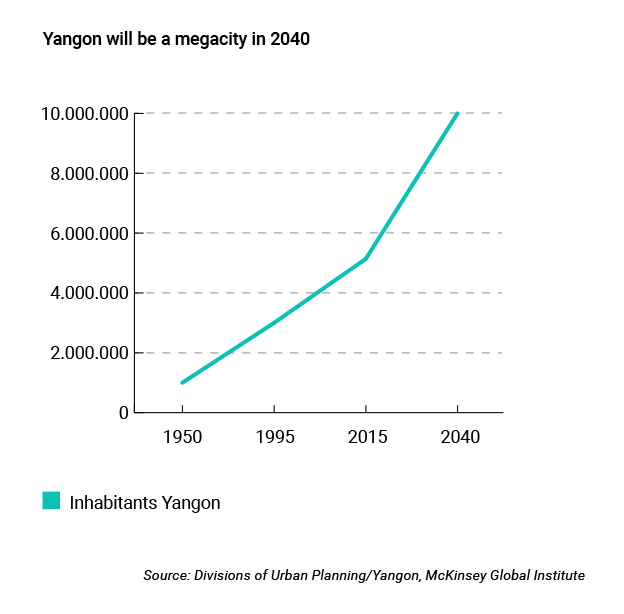

Naypyidaw is six times the size of New York, the roads have 20 lanes and nowhere in the country there’s such an abundance of Wi-Fi and electricity. Just one thing is missing: people. While the population of Yangon is set to double (to 10 million) over the next 25 years, Naypyidaw is a city where people only go to work. At the end of the week or after their meeting is over, most people leave.

The government sees Yangon as a provincial city like any other. So there is hardly any money with which to meet the enormous challenges of urbanisation. Yangon does have an urban planning division, but even responsibility for the architectural heritage is spread across several national ministries.

Which name is used differs between different countries, organisations and media. Generally speaking, the tendency is towards using Myanmar.

When the British colonised what is now Myanmar in 1824, they named the country Burma. In 1989, the junta changed the name to Myanmar. This dictatorial decision was not adopted by most people; governments and media kept on using Burma, following the opposition’s lead. But because Aung San Suu Kyi’s democratically elected party is now governing in the name of Myanmar and has stated that it doesn’t wish to change this name, people are increasingly using Myanmar.

Since the government lifted censorship in 2012, artists and the media are freer than before. But it is too soon to say they have complete freedom. The Ministry of Culture reserves the right to ban or seize artistic expressions it considers in appropriate to Burmese culture. And the fact that a close watch is still being kept on artists was demonstrated at the end of 2015 when a 24-year-old poet was jailed after posting a poem on Facebook that said: ‘I had a portrait of the president tattooed on my penis / my wife hates it.’

In the World Press Freedom Index, Myanmar is in 143rd place out of 180 countries. According to its report, the state media censor themselves out of fear of repression by the state. And not without cause – in 2014, a journalist died in suspicious circumstances after being arrested.